History of Workum

Historical Development

Workum, located on the IJsselmeer coast, approximately 12 kilometers south of Bolsward, is one of the smaller Frisian towns. Originally an agrarian settlement in the southwestern salt marsh, the town developed into an important maritime center in the late Middle Ages. A crucial factor in this development was its location along the Wymerts waterway, now known as Noard and Sud, which connected the Zuiderzee with the Frisian inland lakes.

Along the banks of this waterway, as well as the shipping and drainage canals on either side, the town gradually expanded and densified, incorporating the original agricultural cores into its urban structure. Although parts of the network of canals and waterways have been lost, its pattern remains recognizable in the present-day spatial layout, making Workum one of the most characteristic Frisian water towns.

In the clay-rich areas of Westergo, the first settlements of fishermen and livestock farmers appeared before the beginning of the Common Era. As residential areas, they used natural elevations formed by sedimentation (salt marsh ridges), on which artificial dwelling mounds (terpen) were constructed during periods of severe flooding (transgression phases).

Workum lies at the southernmost edge of this marsh region, on a long north-south running ridge, which separated the waters of the Vlietstroom—after 1200 part of the Zuiderzee—from an eastern lake complex, consisting of Makkumermeer, Parrega’stermeer, and Workumermeer. The presence of several low terpen in the area, such as Yskeburen and Westend, suggests that habitation existed before the year 1000 CE.

Later, as the process of diking the salt marshes began, the number of settlements expanded. Rardieburen, Eninghaburen, and Brandeburen were almost certainly later-established residential areas.

Even within the present-day town, several pre-urban elements can still be found. The terp “Algeraburen”, located on the northeastern side, and the direct surroundings of the Gertrudis Church are also believed to have originated as terp settlements (Kerkeburen).

16th Century: Growth, Conflict, and Reconstruction

To the north of this, at the Merk, a town hall was established during the same period. The exact date when Workum officially became a city is unknown, but it is generally regarded as one of the Frisian towns.

Although in the 15th century, the decline of the Hanseatic League and the rise of the Dutch and Zeelandic cities caused a downturn in Frisian shipping, Workum managed to maintain its economic position, partly due to the emergence of its own shipbuilding industry.

However, in the first quarter of the 16th century, this position was threatened. After a brief period of centralized rule under Albrecht of Saxony, foreign troops once again invaded and plundered the city. The church was destroyed, among other damages, in 1515 and 1523, requiring the complete reconstruction of its tower and sacristy.

It was not until 1524 that the Habsburg governor Schenck van Toutenburg restored central authority in Southwest Friesland, demolishing a fortress built by the Gelderlanders in Algeraburen, as well as a blockhouse, which was likely located at what is now Seburch.

Another consequence of this new governance was the Great Arbitration of 1533, in which the city was assigned the duty of maintaining the sea dikes.

Throughout the 16th century, Workum’s economy gradually recovered, as it increasingly participated in supplying ships and sailors for the Dutch trade and shipping industries.

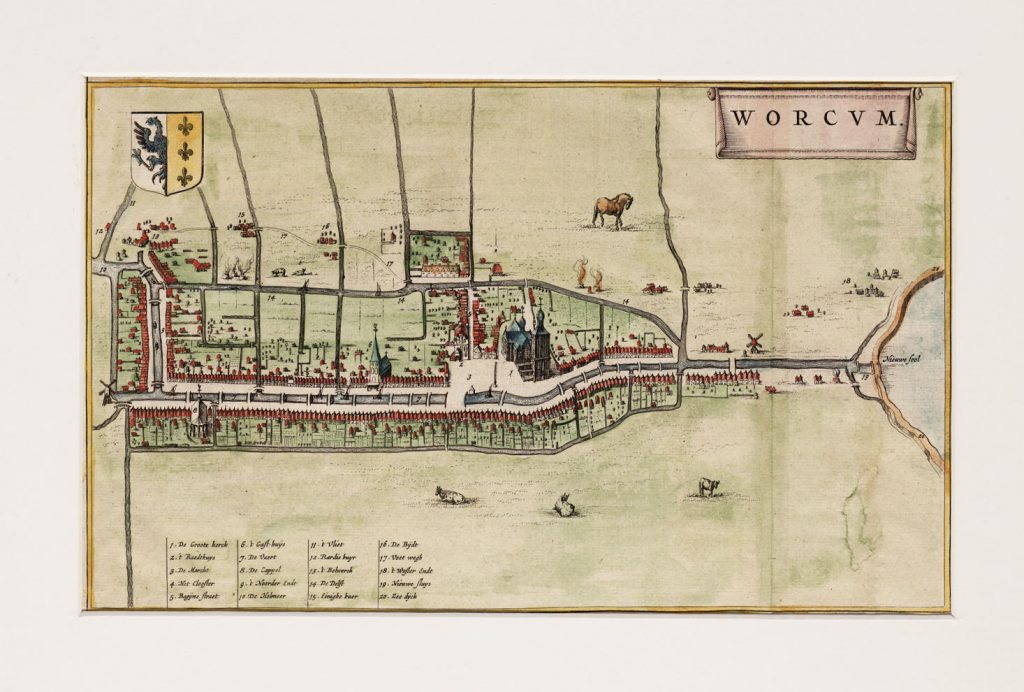

The First Reliable City Map

This period also saw the creation of the first reliable map of the city, produced by Jacob van Deventer around 1560. This map reveals a spatial structure defined by:

– The Wymerts, Dwarsnoard, and Hollemeer waterways.

– The outer canals Droge Dolte and Diepe Dolte.

– The northern boundary marked by the Yskeburenvaart.

Within this fortified layout, several secondary waterways connected the urban buildings along the Wymerts with neighboring districts and the monastery beyond the Dolte.

Van Deventer’s map also depicts:

– The Gertrudis Church, featuring a free-standing tower and sacristy.

– A guesthouse and a chapel, situated on either side of the Wymerts.

– The seaport “Het Zool”, complete with a sluice gate at the southern edge of the city.

Notably, a navigational channel was already in place in the harbor, indicating increasing sedimentation from the Zuiderzee. This eventually led to the poldering of the southern coastal strip, known as the Workumer Nieuwland, which began in 1605 and was completed in 1624.

17th-Century Hydraulic and Architectural Developments

Other major hydraulic engineering projects in the early 17th century included:

– Draining small lakes in the surrounding area (1620–1670).

– Constructing a tow canal to Bolsward (1620–1648).

– Renovating the sea sluice (1658), later referred to as “Nije Sijl”.

Notable buildings from this period include:

– The Frisian House on the Merk (1620), an expansion of the Town Hall.

– The Butter Weighing House, also on the Merk (1650).

– Inthiema House, south of the church, along the Wymerts (ca. 1650).

– Noard 5 residential house (1663).

– Inn “De Zwaan”, at the start of the tow canal (1649).

– The Mennonite Church (1694).

The guesthouse or almshouse managed by the Marienacker Monastery was renovated after the dissolution of the monastery (1580) and was (presumably in 1641) repurposed as a municipal or civic orphanage. The chapel along the Wymerts had to be demolished around 1690 due to structural decay and was replaced by a school building.

The maps of Blaeu (1649) and Schotanus (1664) provide significant additions to Van Deventer’s map. A key difference is visible between the layout west of the Wymerts, featuring deep elongated allotments extending to the Droge Dolte, and the eastern side, where within the broad fortification of the Diepe Dolte, grasslands and vegetable gardens were situated.

The predominantly agrarian hamlets outside the town are now named:

– At the northern city boundary, the terp Algeraburen, which was still called “Het Bolwerck” after the fortification demolished in 1524.

– Further south: Eninghaburen and de Bijdt.

– At the mouth of the Dolten into the Wymerts, the ship mooring site Snakkeburen.

– Finally, near the old sea dike, the terp Westerendt.

Other striking elements include windmills along the city’s edge and lime kilns, with Schotanus recording 17.

Newly emerging industries in 17th-century Workum, although not depicted on the maps, included pottery production, tile manufacturing, and fishing.

Nevertheless, shipping remained the primary source of income.

A quotisatie-cohier (tax register) from 1749 indicates that out of 650 registered professionals:

– 30% made their living from maritime and inland shipping.

– 6% worked in shipbuilding.

– 5% in the ceramics industry.

– 9% in wholesale and retail trade.

– 6% in agriculture.

– 39% in various crafts and services.

The lime kilns and a small salt industry had already almost entirely disappeared by that time.

Gradual Economic Decline in the 18th Century

Over the course of the 18th century, a gradual yet significant economic decline set in.

– The rise of Lemmer as an export center and the strong position of Harlingen’s harbor played a role.

– Most crucially, the decreasing accessibility of Workum for larger ships, due to the continuous silting of the Zool, proved decisive.

– The Anglo-Dutch War (1780–1784), during which many cargo ships were seized, and the French period, which brought maritime trade to a complete halt, marked the end of Workum’s status as a port city.

After this period, Workum served only as a ship supplier and fishing town,

and regional center of agricultural and artisanal activities.

– The spatial landscape underwent little change in the 18th and early 19th centuries.

Buildings that were lost include:

– The monastery complex “Marienacker” (presumably 1790).

– The tower of the former guesthouse on the Wymerts (1757).

– The Inthiemastate (1726).

At the same time, major renovations were carried out on:

– The town hall (1725/1727).

– The inn “De Zwaan”.

The cadastral minute plan (ca. 1830) shows that:

– Along the Nonnestrjitte, the path parallel to the Begine, which connects the church mound to the surrounding pastureland, urban development had taken place.

– Along the Sylspaed, the path from the old core to the sea harbor, densification and expansion had significantly increased.

The former monastery quay along the Dolte had now been developed into residential housing.

At the “Turflan”, workers from the peat-cutting industry in the southeastern Workumerveld and Heidenschap settled.

Further Economic Decline

In the 19th century, the economic decline continued:The ceramic industry, consisting of five pottery and two tile bakeries (1845), largely disappeared due to the rise of enamel production.

Shipbuilding had to scale down considerably, as it could no longer meet the demand for larger vessels.

Only the eel fishery of the Workumer “iel-aken” remained active until around 1900, after which Workum’s markets were taken over by Danish traders.

Although the structure and size of the town remained virtually unchanged, the cityscape underwent a major transformation due to:

– The filling in of the Wymerts (1875), which happened almost simultaneously with the poldering of the Workumermeer.

– The shipping route was permanently diverted outside the city, following the Diepe Dolte and Hollemeer.

19th-Century Buildings

– The gas factory on the Nonnestrjitte (1867, partially demolished in 1976).

– The new city orphanage on the site of the former guesthouse (also 1867).

– The Reformed Church (1887).

– The Roman Catholic Werenfridus Church at “Prystershoek”, on the northern end of the Wymerts (1877), which replaced an earlier church built in 1770.

The cadastral map from 1920 further shows:

– A complex of workers’ housing on the former pastureland behind the orphanage.

– Increased development around the sea sluice and along the extension of the Begine.

– Since 1885, this street ended at the station of the Leeuwarden – Stavoren railway line.

– In 1900, next to the station, the Cooperative Dairy Factory “De Goede Verwachting” was built.

The process of filling in canals and reclaiming agricultural spaces in the city accelerated in the 20th century.

In 1920, the Dwarsnoard was filled in, followed by the Doltemond in 1933, which was then extended into the Hollemeer.

The filled-in section of the Diepe Dolte was subsequently named Houtmolestreekje, after the mill that once stood there.

Additionally, most of the canals from both Dolten to the central city were filled in, leading to the creation of new cross streets and alleys, such as:

– On the west side: Brouwersdyk (formerly Brouwersvaart) and Roggemolensteeg (the canal to the Roggemolen).

– On the east side: Balkfinne, Pothûswyk, and Schoolstraat.

Information About the Coat of Arms of Workum

The coat of arms has been known from the 15th century on city seals. The first seal from 1420 does not yet depict the coat of arms but instead features a Gothic niche, in which St. Gertrude holds a flower in her right hand and a palm branch in her left, with a kneeling monk on either side.

A second seal from 1496 (Van den Bergh) or 1426 (according to the municipality of Nijefurd) does display the coat of arms with the eagle and lilies. The coat of arms appears in the same form on all subsequent seals and depictions.

The origin of the coat of arms is unknown. The half-eagle is a frequently occurring figure in personal coats of arms in Friesland. It may therefore have been derived from a grietman (local governor) or city official of Workum in the 15th century. The lilies could have originated either from a personal coat of arms or from Marian devotion.

The municipality used the coat of arms on official stationery.

Sint Werenfriduskerk, Roman Catholic Cemetery in Workum

Introduction The ROMAN CATHOLIC CEMETERY associated with the St. Werenfriduskerk (1877-78; architect A. Tepe) in Workum was established in 1883. The cemetery is located behind […]

Workumer El

In the past, until around the mid-16th century, Workum had a thriving wool and linen industry. This included a unit of measurement called the “EL” […]

Sleeswijckhuis

Close to the market square, on the main street of Workum, lies the building Noard 5. The main street consists of two rows of houses […]

Tillefonne

The Tillefonne is a church path leading to the Grote or Sint-Gertrudiskerk of Workum. The path was already called Tillefonne in 1560. The name combines […]

Workum Lighthouse

The Workum Lighthouse is the former white, square brick lighthouse or light structure located on the IJsselmeer along the Hylperdyk, at the entrance to Workum’s […]